Tic and habit disorders are syndromes and are a sub-category of neuropsychiatric obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD). These disorders have generally been considered chemical or neurophysiological in origin. They are characterized generally by the inability to inhibit repetitive movements or physical movements. Tourette’s syndrome is a complex neurological disorder of true unknown etiology. At the extreme, the disorder can be clarified as Giles de la Tourette Syndrome (TS) this syndrome can, in extreme cases, be characterized by repetitive outbursts of inappropriate language or cursing coupled with the uncontrollable tics. The individuals suffering from this disorder can sometimes present with co-morbidities such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and in the extreme, spasticity and muscular rigidity. In some cases, a particularly destructive comorbidity called a Habit Disorder (HD) can cause sufferers to present with behaviors such as chronic hair pulling, violent outbursts, and often-violent bruxism. The patients may also suffer from chronic muscle tension.

Of concern, approximately 1-2% of the population in the USA suffers from mild-to-moderate types of tics and a ‘form’ of TS; whereas 200,000 people suffer from severe Tourette’s Syndrome. It has been found that males are 3-4 times more frequently afflicted with TS than females.

Causes of Tourette’s Syndrome

Generally, etiology for these disorders has focused on chemical imbalances, and genetic abnormalities. Some researchers have suggested that a history of depression and prolonged inactivity can produce the symptoms of the disorder including mood, and background personality. Most frequently, situations that cause frustration and impatience can bring about the tics and can sometimes stimulate verbal outbursts or inappropriate behavior. Boredom, lack of self-worth, and drug therapy have all been implicated in bringing about an increase in symptoms.

Activity and behavior modification have also been shown to be moderately effective in reversal of some of the milder cases. Drug therapy including different combinations of neurostimulants and depressants have given some positive results, however, in some of the cases of drug therapy such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) and Haloperidol, an increase in tics has been shown. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale has been used to verify the quantity and quality of tics.

Tourett’s Syndrome (TS) shows higher levels of brain activation during the outbursts and can involve areas of the Basal Ganglia, Frontal lobes and Thalamus. These areas of activation have been shown to be affected by background activation of the brain immediately before the outburst of tics or inappropriate behavior.1-10

Case Report of 19-year old Male with Tourette’s whose Condition Went into Remission Following CBP Corrective Care

Clinical features: A nineteen-year old patient was diagnosed with Tourette’s Syndrome and Chronic tic Disorder at age 14 by a general practitioner (MD). However, he was informally diagnosed with Tourette’s Syndrome at the age of 9 years. The patient was treated with traditional Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy off and on from the ages of 9-14 and then inconsistently from the ages of 14-18. Initially it was reported that this Chiropractic care temporarily alleviated some of his tics but that after the age of 14 his condition progressively worsened.

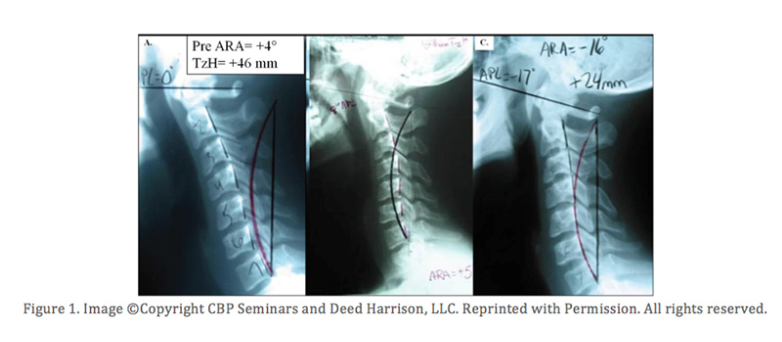

At the age of 14 years, he was treated (unsuccessfully) with Haloperidol for 3.5 of the 5 years after diagnosis. At this time he saw a CBP trained Chiropractor who examined the patient and a lateral cervical radiograph was obtained and showed a cervical kyphosis of 4° measured from C2-C7 using the Harrison Posterior Tangent Method; where normal is 20-42°. The Atlas plane line measured at 3° from horizontal; where normal is 23-29°. And a significant anterior head posture of 46mm was identified; where ideal is 0mm and a normal range is up to 15mm.11

Intervention and Outcome: The patient was treated by a chiropractor utilizing Chiropractic BioPhysics® (CBP®) protocol. The patient received 81 treatments over the course of 3 months. A change from a 4° C2-C7 kyphosis to a 16° C2-C7 lordosis was observed at post-treatment. Additionally, the patient’s forward head posture improved from 46mm anterior to 24mm forward after treatment; a 22mm correction. The changes in patient function was measured using the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale and a 50% improvement in patient function was found as a result of the improvement in the patients cervical kyphosis.

Conclusion: The patient experienced a significant reduction in symptoms. Additionally, the MD prescribing Haloperidol concluded that the reduction in symptoms was significant enough to discontinue the medication. These results indicate that correction of cervical kyphosis in patients with Tourett’s Syndrome may be a desirable clinical outcome as this resulted in the remission of the patients chronic Tourette’s Syndrome.

How Can You Get Help for Your Altered Posture and Spinal Arthritis and Disc Disease and Health Disorders?

Chiropractic BioPhysics® corrective care trained Chiropractors are located throughout the United States and in several international locations. CBP providers have helped thousands of people throughout the world realign their cervical spines back to health, and eliminate a potential source of progressive SADD, chronic neck pain, chronic headaches and migraines, fibromyalgia, and a wide range of other health conditions. If you are serious about your health and the health of your loved ones, contact a CBP trained provider today to see if you qualify for care. The exam and consultation are often FREE. See www.CBPpatient.com for providers in your area.

Source:

References

1. O’Connor K, Brisebois H, Brault M, Robillard S, Loiselle J. Behavioral activity associated with onset in chronic tic and habit disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2003;41(2):241-49

2. Biswal B., Ulmer JL, Krippendorf RL, Harsch HH, Daniels DL, Hyde JS, Haughton VM, Abnormal cerebral activation associated with a motor task in Tourette syndrome. American Journal of Neuroradiology1998;19(8):1509-12

3. Hollander E, Obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders: an overview. Psychiatric Annals 1993;23:355–58.

4. D.W. Woods, R.G. Miltenberger and V.A. Lumley , Habits, tics, and stuttering: Prevalence and relation to anxiety and somatic awareness. Behavior Modification 1996;20:216–225

5. Whalen CK. Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences.© 2001 Elseveir Ltd. Online Edition

6. Buitelaar JK, de Bruin WI, van Rijk PP, van Engeland H. Neuroimaging studies in children with Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder.European Neuropsychopharmacology 1996S;(6):S4

7. Nyakas C,Buwaldab, Luiten PGM. Hypoxia and Brain Development. Progress in Neurobiology 1996;49(1):1-51

8. O’Connor K. A cognitive-behavioral/psychophysiological model of tic disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2002;40(10):1113-1142

9. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Ed. (DSM-IV).1994

10. American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Stastical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed) 1994 ©APA

11. Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Holland B. Comparisons of Lordotic Cervical Spine Curvatures to a Theoretical Ideal Model of the Static Sagittal Cervical Spine. Spine 1996; 21: 667-75